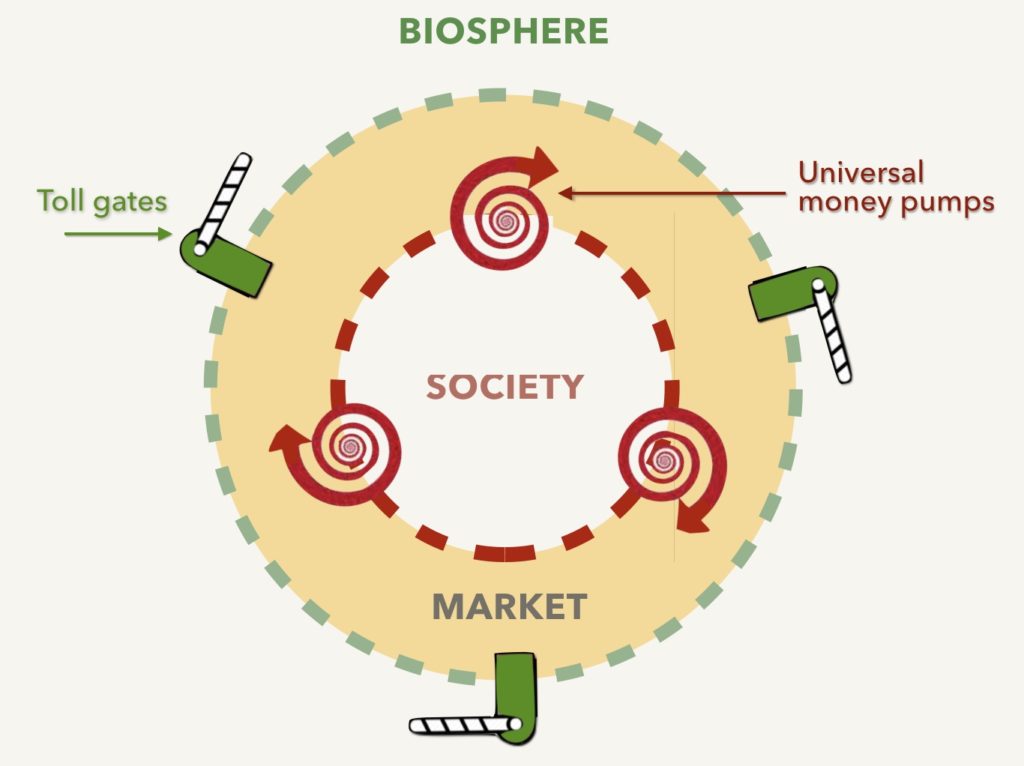

Once toll gates and universal money pumps are added to markets, our economy as a whole would look something like this:

If this seems relatively simple, the consequences would be profound. Within the thresholds of nature and society, or as close as humans can determine them, a market economy would flourish. People would feel more secure, their physical and mental health would improve, and nature would have a chance to bounce back.

To be sure, this economy can’t be built in a day. But it can be built step-by-step, as opportunities arise — for example, after crises, of which there will be many. Think of Social Security, which began small in 1935 and now, along with Medicare and other social insurance programs, makes up ten percent of GDP. And think of intellectual property, a relatively new set of property rights that today accounts for over half the market value of several major industries. Might universal property spread as quickly? If it did, the eventual result would be a hybrid economy.

For many years, political debate in the West has been gridlocked between advocates of less government and more. A market economy interspersed with universal property would bypass that polarized stalemate. It would be a hybrid of capitalism, socialism and ecological science, blending the best of each.

Hybrids have much to commend them. In biology, their physiological vigor is often greater than their progenitors’. Similarly, in human societies, economies that produce the most well-being, like those in Scandinavia, blend markets and private enterprise with wage solidarity and generous welfare states.

The virtues of universal property include not only what it adds to markets, but just as importantly, what it preserves. With universal and individual property in balance, markets would retain their vitality and dynamism. Prices would still send signals, innovation would still flourish, and governments would do roughly what they do now. In short, we’d get the upsides of markets without their tragic flaws.