In addition to the economic and ecological arguments for universal property, there is a strong moral case to be made. It rests on the recognition that living humans have responsibilities to each other, to other species, and to future generations.

This is not a new idea. As conservative philosopher Edmund Burke wrote in the 18th century, society is a contract “between those who are living, those who are dead, and those who are to be born.” Yet as we know, markets in their current configuration include no such contract. To the contrary, by disproportionately benefiting those who own the most property today, they consistently undermine both our inter- and intra-generational responsibilities.

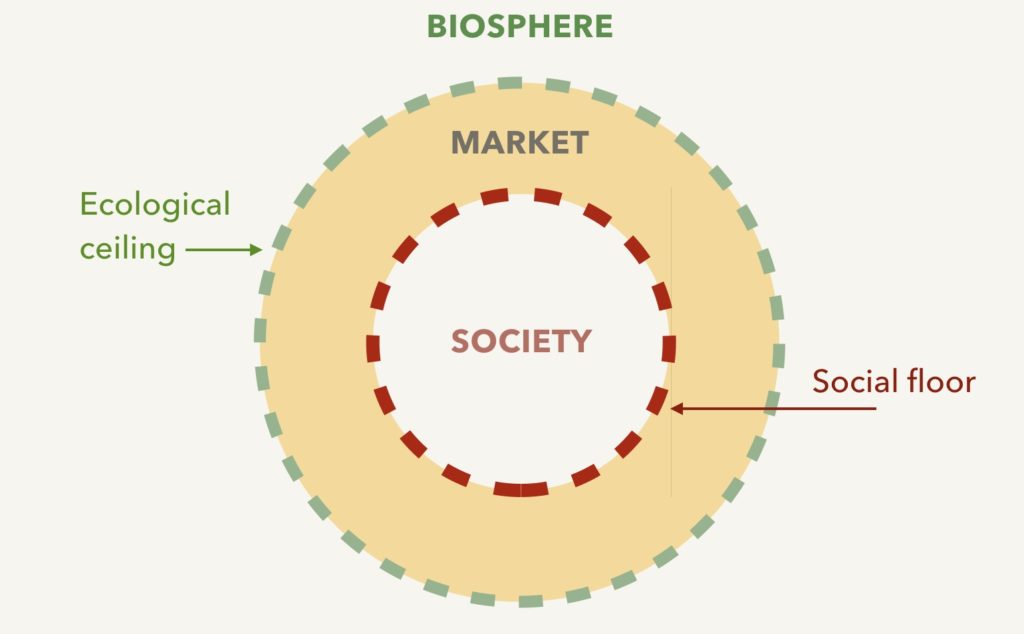

One way to think about human responsibility and markets, offered by British economist Kate Raworth, is to situate our economy inside a doughnut bounded by an outer ecological ceiling and an inner social floor. In order to fulfill our multi-generational responsibilities, we need to keep markets operating between those boundaries. But how? Universal property supplies an answer.